News & Stories

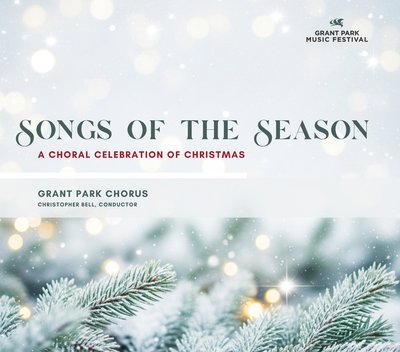

Songs of the Season: A Choral Celebration of Christmas

Read post: Songs of the Season: A Choral Celebration of Christmas

Grant Park Music Festival Raises $1.3 Million in Support of Artistic and Educational Programming

Read post: Grant Park Music Festival Raises $1.3 Million in Support of Artistic and Educational Programming

My Summer with the Festival Fellows

Read post: My Summer with the Festival Fellows

Meet Giancarlo Guerrero

Read post: Meet Giancarlo Guerrero

Meet the Festival's 2025 String Fellows

Read post: Meet the Festival's 2025 String Fellows